Mature Incarnations

Harry Partch's Late Period

The final portion of Harry Partch’s artistic career, from the early 1950s to the end of his life in 1974, was characterized by the increasing dramatic scope and “corporeality” (in Partch’s words; more on this later) of his compositions, as well as a shift in thinking away from Americana subjects and back to global, non-Western influences.

In 1949, Partch’s Genesis of Music was published. This treatise criticized the equal temperament tuning system commonplace in Western music since the time of J.S. Bach, which, from his perspective, had limited composers by not allowing them to make use of scales with non-Western musical origins. The treatise also supplied a technical explanation of Partch’s own just intonation tuning system.

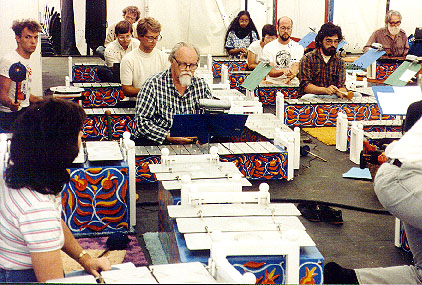

Two years after Genesis was published, Partch returned to California. There, he continued building instruments, now with a particular focus on percussion instruments; these include a bass marimba, as well as more esoterically-named instruments like the “spoils of war,” so-called for the inclusion of seven freely hanging artillery casings intended to be struck by the player of the instrument. During this time, Partch began writing pieces for large ensemble that made extensive use of his new percussion instruments, such as Plectra and Percussion Dances (1957).

Partch's Spoils of War

Partch's Spoils of War

In 1956, Partch moved to Urbana, where he worked at the University of Illinois and staged productions of Water! Water! and Revelation in the Courthouse Park, two stage dramas requiring full orchestras made up of nearly all of his previously built instruments. These works were some of the first pieces in his “corporeal” style. From Partch’s perspective, corporeality referred to a certain physicality in music – corporeal music was stylistically unorthodox and dramatic, in the theatrical sense of the word. Partch’s instruments were in full view of the audience, and played a crucial visual role in the performance. They were not merely a means to an end for producing a given sound: Seeing the performers interact with these strange and beautiful objects was part of Partch’s artistic project.

a filmed version of Harry Partch's Delusion of the Fury (1969)

After permanently relocating to California in 1962, Partch worked for multiple years on what would be his largest-scale work: Delusion of the Fury (premiered 1969). In several ways, this stage play is the culmination of Partch’s life’s work. All of the music is microtonal, and the piece is written for the single largest ensemble of his custom-built instruments out of all of his compositions. For this late work, the pendulum of Partch’s taste swung back from Americana-related text to the non-Western poetry and stories he set in his early “monophonic” experiments. In Delusion, Partch adapts both a tragic Japanese Noh story and then a farcical Ethiopian folk tale. In keeping with Partch’s interest in ancient Greek culture, the ordering of the aforementioned sections within the work may be a nod to the practice in ancient Greek theatre of following a tragedy with a satyr play (which had comic elements and happy endings.)

In 1973, despite worsening physical and mental health, Partch completed the score for The Dreamer that Remains, a documentary film about his own life. One year later, he died of a heart attack.

Lou Harrison's Late Period

The later years of Lou Harrison’s compositional career are defined by a continuously tighter focus on gamelan music as a source of artistic inspiration.

In 1967, Harrison came to know William Colvig, who would become his life partner and collaborate with Harrison on the building and tuning of novel instruments. One of the most fascinating of these was constructed in 1971 – a set of various metal objects, including garbage cans, oxygen tanks, and tin cans, all tuned to a D major scale in just intonation. Harrison named it “An American Gamelan,” since the collection of disparate metal objects bore a sideways resemblance to the Indonesian ensemble of tuned gongs he was so familiar with. Over the following three years, Harrison wrote three pieces that made use of the American Gamelan, including the Suite for Violin and American Gamelan (1974).

Lou Harrison's American Gamelan

Lou Harrison's American Gamelan

The Suite typifies Harrison’s style during this late period, as it encompasses many of the forms and styles he had been exposed to and taken inspiration from throughout his life. It includes an estampie (a dance form from medieval Europe), three Jhala movements – the Jhala is a form from Northern Indian classical music featuring a melodic drone – and a chaconne, a Baroque form made up of melodic variations over a repeated bass line. Throughout the Suite, Harrison combines a free melodic line in the violin with a repetitive, hypnotic pattern in the gamelan accompaniment, effectively combining features of both Western and non-Western musical traditions.

Lou Harrison's Concerto for Piano with Javanese Gamelan (1987)

Studies with K. R. T. Wasitodiningrat, a famed Javanese gamelan player from Java, in 1975, inspired Harrison to begin writing music intended to be performed by traditional gamelan ensembles. In some of these works, Harrison employed his familiar technique of combining disparate musical traditions by writing for gamelan with a Western instrument as the soloist. For instance, in the Concerto for Piano with Javanese Gamelan (1987), Harrison employs a familiar Western instrument and form but calls for the piano to be re-tuned to match the non-Western gamelan, achieving a synthesis of styles.

By the mid-1990s, Harrison had stopped composing to focus on caring for Colvig as his health deteriorated. Colvig died in 2000, and Harrison died three years later while traveling to a festival of his own music.

Table of Contents

- Website Overview

- Background

- First Experiments

- Developing Styles

- Mature Incarnations || You Are Here!

- Legacies & Impact

- Bibliography