Background

Harry Partch's early musical experiences laid a foundation that profoundly influenced his artistic evolution. Born in California to Presbyterian missionaries who had spent time in China, Partch was exposed to a remarkable diversity of musical traditions from an early age. His upbringing in the American Southwest immersed him in a wide variety of sounds, many of which originated from non-Western traditions. These sounds ranged from Christian hymns and Chinese lullabies to music heard as part of Yaqui Native American rituals and Congo puberty ceremonies. These varied cultural encounters instilled in him an appreciation for the possibilities inherent to non-Western musical expressions, including divisions of the octave other than the standard 12 tones.

Partch's formal musical training consisted of studying instruments such as the piano, organ, mandolin, and cornet, resulting in an understanding of a variety of methods of sound production, which would be useful in his later instrument-building experiments. His proficiency on the piano was such that he could accompany silent films in Albuquerque, New Mexico during his youth. However, it was his return to California in 1920 and subsequent years spent as a proofreader, piano teacher, and violist that allowed him to truly begin exploring and internalizing the musical influences surrounding him.

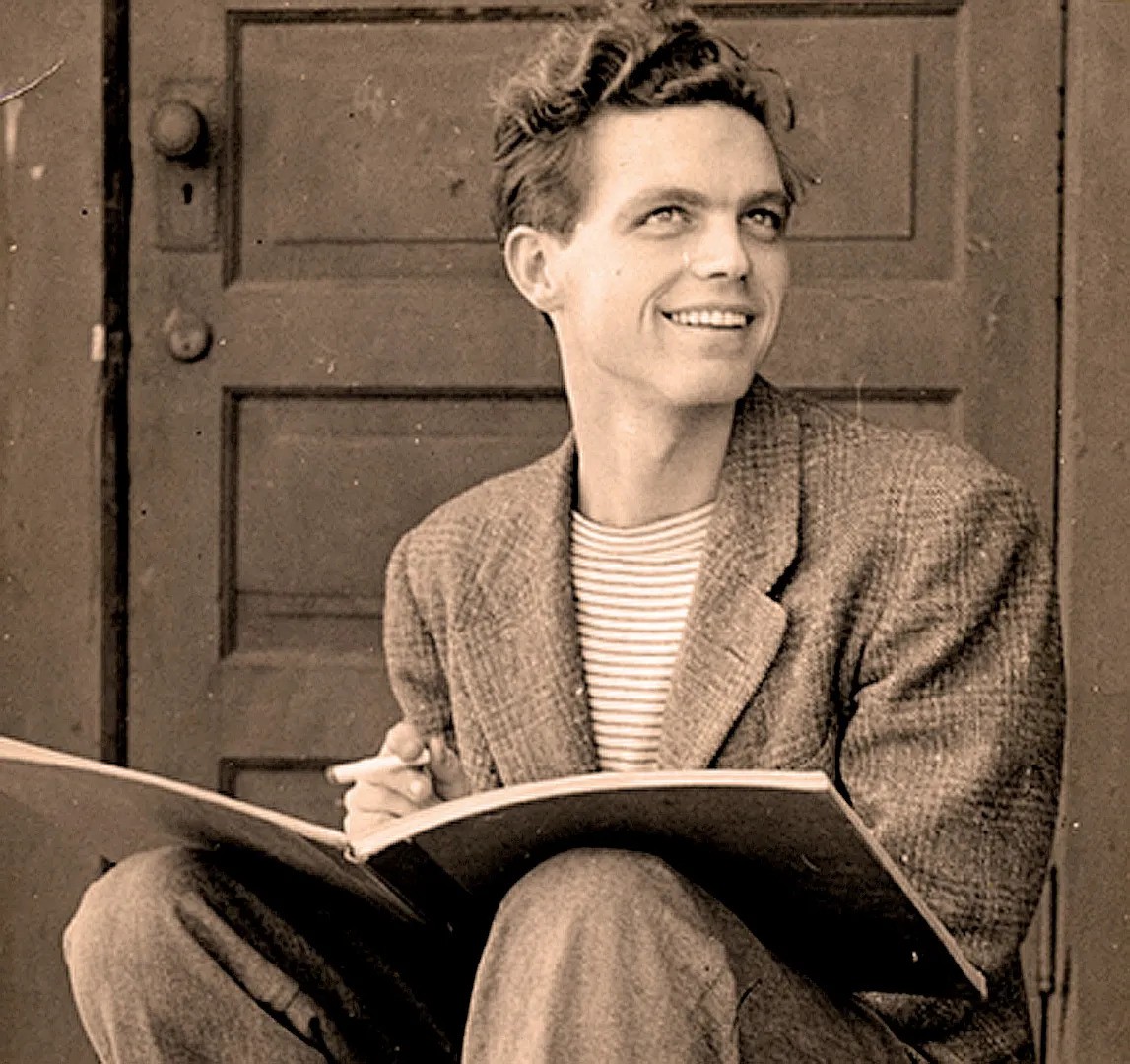

a young Harry Partch (c. 1919)

a young Harry Partch (c. 1919)

Frustrated by the limitations of his formal music education at the University of Southern California, which he felt neglected music's acoustical foundations, Partch embarked on a journey of independent research into intonation. This search eventually led him to Hermann von Helmholtz's seminal work "On the Sensations of Tone," a discovery that revolutionized his musical thinking. Helmholtz's advocacy for the use of just intonation and translator A.J. Ellis's discussions of experimental keyboard instruments from the 19th century profoundly impacted Partch's future approach to tuning systems and musical composition. Partch's diverse musical upbringing, his hands-on experience with various instruments, and his independent scholarly exploration of acoustics and tuning systems all helped set the stage for his later groundbreaking work in instrument-building and microtonal music. His early encounters with different musical cultures and his dissatisfaction with conventional Western tuning systems would become driving forces behind his experiments with new tunings and the creation of his own unique instruments, which played a pivotal role in shaping his distinctive musical language.

Much like Partch, Lou Harrison's early musical experiences also played a pivotal role in shaping his musical aesthetic. In particular, they informed his approach to instrument-building and laid the groundwork for his use of elements from non-Western musical traditions in his compositions. Growing up in northern California, Harrison's musical journey began with studies in piano and violin. During this time, before he had even graduated from high school, he began composing keyboard and chamber works. These early works demonstrate his interest in musical experimentation, even at a young age, as they include compositions using quarter-tones. His diverse musical interests continued to expand during his time at San Francisco State College, where he studied and played a multitude of instruments, such as the horn, clarinet, harpsichord, and recorder, which he played in an early music consort.

a young Lou Harrison (c. 1930s)

a young Lou Harrison (c. 1930s)

One of the most important moments in Harrison's musical development came in 1935, during his first year of college, when he enrolled in composer Henry Cowell’s course "Music of the Peoples of the World." In this class, he was introduced to Indonesian gamelan music, a musical tradition native to Bali involving complex polyrhythmic and timbral interaction between many tuned gongs. This resulted in a lifelong fascination with gamelan music. The instrument’s rhythms, timbres, and non-traditional tuning system influenced Harrison's compositional style and led to extensive works for gamelan ensembles and various gamelan-inflected pieces in the later stages of his career.

Harrison's connection to non-Western music was reinforced when he attended a concert by a Balinese gamelan group at the Golden Gate Exposition in 1939, an experience that solidified his commitment to exploring and incorporating diverse musical traditions into his compositions. Alongside continued studies in composition with Cowell, Harrison also immersed himself in the works of Charles Ives and delved into American Indian and early Californian culture (think Gold Rush-era Forty-niners), which became recurring themes in his compositions.

Harrison's later interest in instrument-building stemmed from these early experiences and musical explorations. His exposure to a wide range of instruments and musical cultures, particularly Balinese gamelan, inspired him to develop custom-made instruments and experiment with alternative tuning systems that expanded the sonic possibilities in his compositions by incorporating elements of non-Western music into the Western classical tradition.

Table of Contents

- Website Overview

- Background || You Are Here!

- First Experiments

- Developing Styles

- Mature Incarnations

- Legacies & Impact

- Bibliography